(written for CreepyLA.com)

It’s my favorite time of year again, when the skies are looking a little bit grayer and the air feels a little bit colder than it did just a few weeks ago. Summer has slipped away, but winter hasn’t yet begun. (‘Fall’ is something of an urban legend here in southern California— a rumor spread by those who’ve come from distant places, one that’s never quite believed in by the natives.) It’s at this particular time of the year, midway between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice, when the earth’s tilting axis inclines us away from the warmth of the sun, that the veil between the world of the living and that of the dead grows thin.

It’s my favorite time of year again, when the skies are looking a little bit grayer and the air feels a little bit colder than it did just a few weeks ago. Summer has slipped away, but winter hasn’t yet begun. (‘Fall’ is something of an urban legend here in southern California— a rumor spread by those who’ve come from distant places, one that’s never quite believed in by the natives.) It’s at this particular time of the year, midway between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice, when the earth’s tilting axis inclines us away from the warmth of the sun, that the veil between the world of the living and that of the dead grows thin.

It’s something we’ve sensed for ages. Pagan Europe called it Samhain: a festival to mark the beginning of the dark half of the year. The medieval Catholic church repackaged the old observance as All Souls’ Day, and the folk tradition we now know as Halloween grew up from the resultant tangle of beliefs. A similar process of syncretization occurred on this continent when ecclesiastical memes exported from Spain collided with indigenous practices and el Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, began its ongoing evolution.

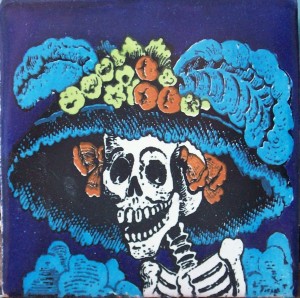

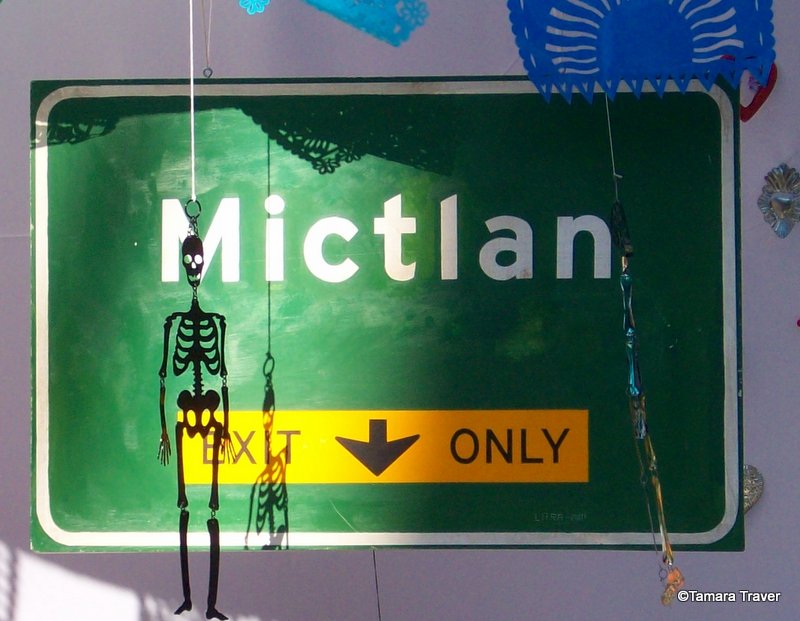

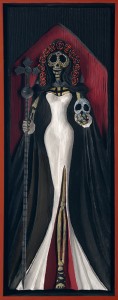

The holiday’s roots run deep in Mexico. That nation’s Aztec ancestors once celebrated a month-long festival in honor of their death goddess Mictlancihuatl, and her shadow can still be seen in the calaca costumes and colorful Catrinas that abound today. While few in L.A. have the option of holding a nocturnal graveside vigil to welcome home returning souls, many other traditional trappings—such as candlelit altars and sugar skulls, marigolds and copal incense—are here to experience at any number of local events. Olvera Street’s procession showcases Mexican heritage, but the massively-attended party at Hollywood Forever Cemetery allows for more avant-garde variations on the theme. Like everything else in Los Angeles, our Day of the Dead is flexible and subject to reinvention, ours to fashion in any way we please.

The holiday’s roots run deep in Mexico. That nation’s Aztec ancestors once celebrated a month-long festival in honor of their death goddess Mictlancihuatl, and her shadow can still be seen in the calaca costumes and colorful Catrinas that abound today. While few in L.A. have the option of holding a nocturnal graveside vigil to welcome home returning souls, many other traditional trappings—such as candlelit altars and sugar skulls, marigolds and copal incense—are here to experience at any number of local events. Olvera Street’s procession showcases Mexican heritage, but the massively-attended party at Hollywood Forever Cemetery allows for more avant-garde variations on the theme. Like everything else in Los Angeles, our Day of the Dead is flexible and subject to reinvention, ours to fashion in any way we please.

Even so, at its core el Dia de los Muertos remains unchanged. It’s our annual chance to remind those we’ve lost that we remember them, as well as to mock the specter of death that stalks us all, at every moment of our lives. Our most fundamental human wish—to hold onto some small part of what death insists on taking away—is summed up by images of skeletons celebrating in joyous defiance of life’s harshest truth. The offerings of food and drink left out for departed friends and family help us to reconnect, once per year, with the ghosts of our past… who must be gone again by morning.